Part 4: Iran

Hijabs, Hot-Pants & Booze…

When we woke up after a decidedly mediocre night of sleep (the Turkish military didn’t allow us to put up a tent in their back yard for some reason) we were both a bit nervous. How would the Turkish coup-d’état affect the border entry process? How would things work with the fancy Carnet de Passage we organized in Germany? And last but not least, how likely was it that they would find our two bottles of smuggled Turkish quality vodka? You see, Iran’s full name is not Iran but the Islamic Republic of Iran, which gives you a small indication of just how serious some of its inhabitants take their religion. And as you may know, Muslims do not drink alcohol, ever (unless you are behind closed doors and below a roof where the all-powerful Allah who shaped the world and the universe and everything apparently cannot see and judge you). So the chances of us having to pay a fine, end up in jail or worse, get send back to wherever we came from were pretty big if they would find our contraband.

When we were still in Turkey we contemplated various ways to bring these glass bundles of joy into the country without suffering one of the aforementioned consequences. We decided we wanted to go for plausible deniability, which is why the plan to re-package the vodka in plastic bags and fill our bull-bar (or rectal cavities) with them died an early death. We also contemplated the option of wrapping the bottles in gift wrapping paper, but in the end decided to go for the stupid tourist option and put them under one of our car seats next to some water bottles, simply feigning to have forgotten them if Iranian customs would catch us.

Border service

So as you can imagine, we were a bit worried, but decided to get in and go for it. The first post opened about an hour and a half later than promised, but we imagined the Turks needed a well-deserved cup of tea before starting a long working day. When the gates finally opened, we first needed to check out from Turkey. A couple of stamps did the trick and after a few last selfies with Turkish customs officials the second gate opened before us. The first thing we saw was a two meters tall bearded Iranian soldier, looking a bit grumpy. He directed us to a small office, which is where the fun started. In this little office, we were greeted by a guy who immediately offered us a cup of tea, and explained the border crossing process in proper English. After having our passports registered, we got our first stamp and a bit of explanation on the difference between a Khomeini and a Khamenei (the great religious leaders of Iran). The first customs official introduced us to Hamid, a friendly Iranian in his late 40’s, who greeted us with a heartwarming “welcome to Iran”. Hamid was a fantastic human being, and he would help us, almost like a private tour guide, during the next two hours through the intricacies of the Iranian border process. Where on the Turkish side we were still met with a bit of skepticism, the Iranians were more than welcoming, leaving us with an impression we will always be grateful for. The process itself was sometimes slightly complicated and inefficient, but this had more to do with bringing our own vehicle over the border than with the customs process itself, which Jos had experienced before. After the registration of our passport, Hamid helped us to get to the next station, where the Carnet de Passage was getting some very thorough treatment. Never had we seen someone so motivated with his ink and stamps and after everything was said and done, the document had received at least 10 stamps on various pages and was registered in various offline and online systems. When the Carnet had been properly decorated with official looking stuff, Hamid took us to the next stop, every time explaining in his best English what we would be doing there.

Even so, it wasn’t quite clear what the next stop was for. Our passports were registered by hand again in a big book for which we had to pay our first fees in Iranian Rials. Or Tomans. You see, the thing with Iranian money is that it will always be somewhat of a mystery, because it is a bit of a challenge to get used to (apart from the fact that you get about a 50% better exchange rate on the black market than in an official bank). The paper money (coins are virtually non-existent in Iran) mentions the currency value in Rials, although, for some unclear reason, the Iranians then divide that number by ten and call it Toman. So when an Iranian person asks for money, you always have to confirm what he or she actually means.

Combined with the questionable English skills of some of the lower educated Iranians, this can lead to some hilarious situations, for example like when we were asked to pay a dinner with Iranian money worth 175,- € (which seemed a tad too much for the decidedly simple chicken kebab and rice we had eaten). One way or the other, we simply started to call the currency either Khomeini’s, revolutionary Rupees or Obermufties, and some of them were due to be paid to the customs official for whatever (probably legitimate) reason. Of course we didn’t bring anything other than our trusted Euro’s to the party, so Hamid jumped up and got us a big stack of Khomeini’s in exchange for our Euro’s right away. He even apologized for the bad exchange rate he got, which was about 37.000 Rials per Euro (which wasn’t all that bad, no-one we talked to during our visit got more than 41.000 Rials for their Euro). We were happy as we could be, as we thought the exchange rate would still be somewhat similar to the 2012 level, when Jos got about 25.000 revolutionary Rupees for his Euro. Anyway, after paying the customs official with our newly found Khomeini’s, Hamid inquired whether we wanted to buy some insurance for driving around his beautiful country. We decided that it would depend a bit on the price the Iranians wanted to have for it, as we already paid over Eu 80,- in Turkey and noticed driving around safely with a warm fuzzy feeling in our tummies could become very costly if every country asked us the same. Hamid again did his thing and before we knew it, he had scouted the insurance market and came back with the best offer he was able to find, which was about 8€,-. Done deal we said, and Hamid helped Stefan to get through the challenges of getting a car insured in Iran within minutes.

Insured, stamped and properly dehydrated (no that’s not true, we got offered tea at almost every customs post) it was time for the inspection of the car. The first question from a more serious customs agent was the one we had feared all along: do you carry any alcohol with you? No, Jos answered immediately without blinking. Luckily he was very convincing, emphasizing his confidence with opening the rear car door with a theatrically big gesture: here, have a look! To be honest, this trick has worked with every customs agent, as none of them really wants to go through our dirty and dusty clothes, camping gear and canned food. So after a quick glance into the car, the customs agent trusted our pretty blue eyes and called it a day. In the meanwhile, a bunch of children had gathered around the funny looking foreigners in the mini-jeep. We got some of the candy, Katharina had been nice enough to organize for us and started distributing them. It took about three minutes before Hamid came running towards us, looking much more worried than we had seen him before. You cannot do that in Iran, you really shouldn’t, he said. A little confused, we asked him what he actually meant and before we knew it he got a piece of brown-colored substance we gave to one of the kids out of his pocket and said: here, this, you cannot give hashish to children, that is not allowed in Iran. Stefan looked at Jos and said: you didn’t, did you? Of course not, Jos laughed, that is licorice, a popular type of candy from the Netherlands. In order to prove it we ate some of it and offered Hamid some as well, which he hesitantly accepted. Ok, Hammid said visibly relieved, that is not hash. Right, that would have been plain stupid now wouldn’t it? Our journey at the border had come to an end, which meant it was time to shake Hammid’s hand and thank him a thousand times for his kind help. He offered us his phone number and told us to we could call him anytime of the day for support, would we get into any issues in Iran. We will never forget his kind help and he proved to be the first few drops in a wave of friendliness which would be bestowed upon us by the people of Iran. We have never been, and may never be, treated so kindly at a border crossing as here. Thanks a thousand times Hamid!

After driving through the final gate we were greeted by many more friendly faces. We decided to get to Tabriz, the first major city on the Iranian side of the border. But first, we needed to get petrol. Lots and lots of petrol. Not only because our Terrano demanded a great amount of it in order to cross the Iranian mountains, but also because the Iranian petrol, or benzin as they call it here, is of such a low quality (octane rating RON 80) that simply putting in vodka would probably have provided more energy per liter. We drove into the first village and got some undefined quality petrol for about 14.000 Rials, which was a “preposterous” 38 cents per liter (what would later on become closer to 10.000 Rial or 25 cents). After having filled up our tank again we drove off to Urmia, which Hamid had told us was the prettiest route to Tabriz. And he was right. We drove through a breathtakingly beautiful mountainous landscape over what we thought at the time were pretty terrible roads (obviously we had never been in Turkmenistan or Uzbekistan before, more on that later). After having been able to find some lunch in Urmia, which was a bit of a hassle, we drove off to the great Urmia lake. This lake, which hosts many Iranian tourists, was crossed by a long bridge. Sadly, there was little to see, as most of the road was sided with large rocks, preventing us from viewing what was behind it. However, when we were finally able to see beyond the rocks, we noted that most of the water had evaporated, leaving a great salty plain which was a bit underwhelming and overwhelming at the same time. We were met with a nice surprise though, when we finally arrived at the other end of the bridge at the toll port, where the toll agent didn’t want to accept any money from us, simply saying “welcome to Iran my friends”.

After being treated to a wonderful sunset we arrived in the bustling traffic of Tabriz, which took a fair bit of courage to navigate. Here, as opposed to in Istanbul, not only the taxi drivers but basically everyone was driving kamikaze style, a bit like you would imagine Italians driving when drunk. No-one showed any respect for our bull-bar, which we were lucky enough not to have used. After finally having arrived at the cheap hostel we were welcomed by the friendly and well-traveled Mohammed, who was the helpful chef-de-hotel. After having shared some of our fresh experiences with Iranian people, landscapes and traffic, he offered us two of his room keys, as if he were offering the blue and red pill to Neo in the film The Matrix. We were a little bit confused about his mysteriousness, but soon found out what he was trying to tell us. When we turned the keys to the rooms we saw that they were exactly the same, except for one minute difference: one had a double bed and the other room had single beds. This was Mohammed’s subtle was of asking whether we were a gay couple (more about that assumption later), which is frowned upon in the Islamic Republic as much as it is in strict Jewish and Christian communities. Not being gay and all, we chose the room with the single beds and headed upstairs. Stefan started working on our nicest pictures and gigabytes of film we had recorded with our Go Pro, while Jos went downstairs to get some drinks. This is where we first saw another rally team, 4 guys from Australia driving a Fiat Panda (yep, it will fit four adults, contrary to popular belief). We exchanged a few quick stories about our experiences and called it a night.

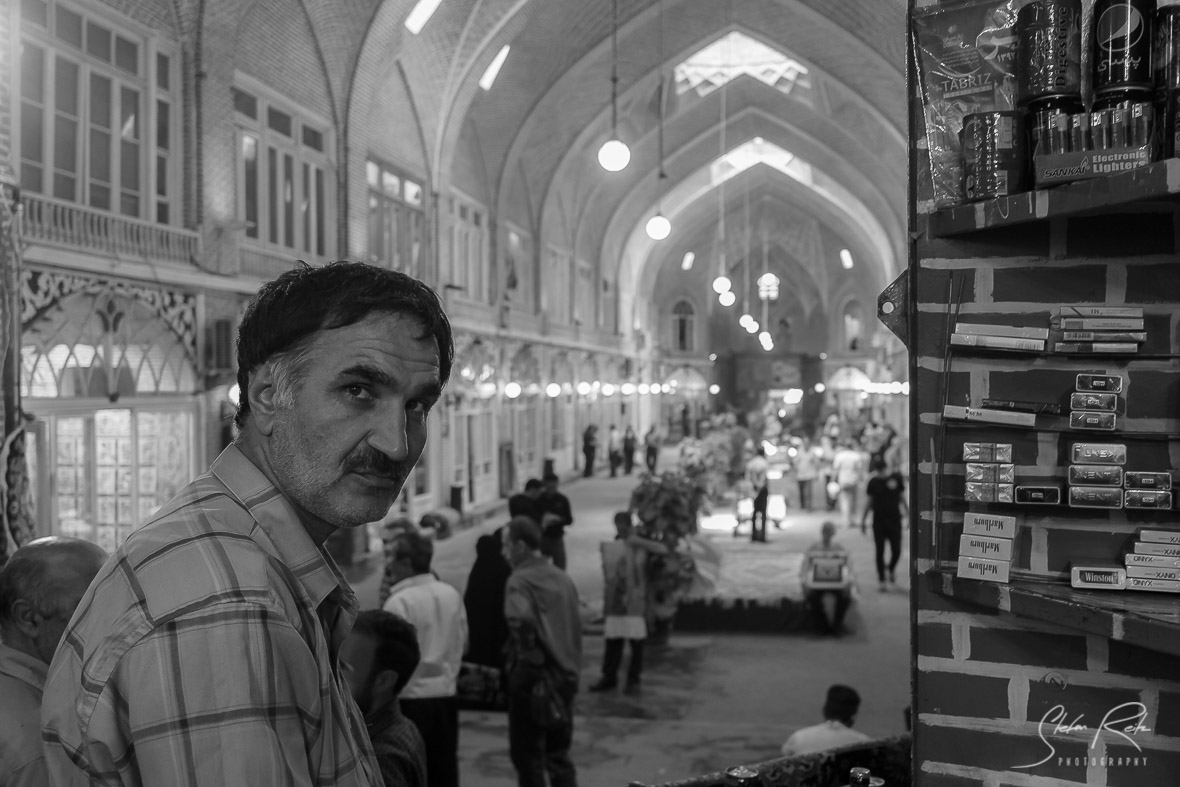

The next day we decided to go out to check prices for some new tires, as we felt a bit uncomfortable with the state ours were in. Even though the Iranians had been able to fix out old one within 2 minutes for about 2 Euro, the profile was we had left on some of them was only a couple of millimeters. The guys at the hostel introduced us to, who we later learned, were the famous Tabriz tour guide Nasser Khan and his brother. They offered their help and before we knew it we were walking down “Auto parts Alley” in Tabriz where everything car related, from tires to car mirrors and from lighting to car seats, could be had. Although these guys obviously didn’t get to the chapter about business differentiation in the big book of marketing yet (basically everyone sold the same items as their neighbor), everything we wanted was at our disposal. Before long, we had some price quotes for the new tires, which were all higher than our predetermined budget of 75 Euro per tire. After having walked around for an hour or two we decided we were just going to wing it and trust that karma would help us once more getting through to Mongolia (as in, without any new tires). The thanked mister Khan and headed off to the Tabriz bazaar for some shopping and pictures. Little did we know what was about to hit us in the bazaar.

It took only a few minutes before we looked at one another and said: what the f*ck is this? Why the strong language I hear you think, but this was something we’ve never experienced and may never experience in our lives again. Long story short, Stefan was wearing hot pants. Well not actual hot pants like in those cheeky movies that pollute the internets nowadays, but pretty standard shorts, cut right above the knees. But to the Iranians, that is pretty much what he was wearing, we could see it in their eyes, literally. As you may know, those funny mullahs which kind of rule this beautiful country a bit since the revolution of ‘79, have pretty ugly looking knees. So in order to not be confronted with that uncomfortable reality, they simply chose to give anyone who is showing their knees in public 99 whips with a stick or a couple of months in jail. That’ll teach them, they must have thought, and went on their merry way. However, having grown up in a free country like Germany, Stefan thought it would be completely appropriate to wear something sexy like that in public. It is impossible to express the attention he received. People just left their baby carriage in the middle of the street and ran to see what was happening. Woman covered from head to toe in black hijabs were blushing to the extent steam came out of their ears. Grown men were twisting their neck to get a good look at Stefan’s decidedly good looking knee-structure. This was a small revolution taking place on the streets of Tabriz, utter and complete mayhem. Jos looked around him from behind his sunglasses and noticed that everyone and their grandmother had a laser focus on one spot and one spot only, Stefan’s naked knee joints. It took us a couple of moments to get used to it, but before long Stefan was completely absolved in his new-found role as arousing “hot hunk”. This is how blonde Russian girls must feel in bikinis on a Turkish beach, he said. Jos concurred and admitted he was a little bit jealous, with his properly covered knees.

We decided not to push our faith much more (apparently foreigners have a bit more freedom from the police to show their naked skin in public, but not much) and went into the bazaar. It took about five minutes for people to start talking to us out of the blue. What’s your name, Adib, a friendly and smart looking 18 year old Iranian giant from Yazd, asked us. He was there with his family on holiday and asked us how we liked Tabriz. Very much, said Stefan for reasons you can imagine, I feel like a movie star! We discussed the city a bit and soon the conversation turned to politics. His mother joined the conversation and apologized to us for the Iranian regime and for the terror attack conducted by a German from Iranian decent in Munich a week or two before. This was not the first time we had been offered apologies from Iranian’s for their government, as it happened a few times before and after that conversation. We got the impression that President Rohani, although relatively popular in the West (which, granted, wasn’t too much of a challenge after the regime of I’m-a-dinner-jacket in the years before), hasn’t enjoyed the same success with the Iranians. The economy has been hit hard by western sanctions (see also the heavily decreased exchange rate), and Rohani hasn’t gotten the support from the Mullahs to put through his ambitious reforms for the people. We tried not to take too much of a strong standpoint, as again, we’re not here to make this our fight. Adib’s mother expressed something else, which we heard a couple of times over the course of our visit to the country, something which also impressed us quite a bit: “please tell everyone at home we are not terrorists”. Duly noted, and yes we definitely will. We were happy that we were able to steer the conversation in a different direction, and before we knew it we got invited to one of the family weddings. Sadly, this wedding would take place in about one and a half months, which meant we would be somewhere in east Asia or back home again when it would take place. Nevertheless, we thanked the family wholeheartedly for their openness and kindness and, after an exchange of phone numbers, we said our goodbyes and headed off to some little stairs outside the bazaar.

It took only about a minute after we had lit up our cigarette to hear the same phrase again (we would hear this a lot, together with “Welcome to Iran”, “Where do you come from”, “Thank you” and even “Good morning” in the middle of the evening). My name is Stefan, I am from Germany, Stefan said. And I am Jos, what’s your name? The Iranian youngsters were interested in football, and were able to mention quite a few of our most famous players. However, what made this exchange noteworthy to us was their next curiosity: Where did you guys meet? The internet? Again, the message was loud and clear: so, are you gay? Somehow Iran is not used to two blokes travelling together without their spouses, and we would be confused with gay guys a lot more during our trip. Nevertheless, the twinkle in their eyes when asking this question is something we will never forget. Jos felt the need to confirm his heterosexuality by showing a picture of him and Katharina, explaining they were married (the concept of a girlfriend is also not completely understood by every Iranian). After we settled that once and for all, we decided to get into the bazaar again to actually experience what this beautiful market hall was all about.

After having taken some more pictures, Jos said to Stefan: we need a flag. Stefan knew what he was talking about, the positive experiences we had in Turkey carrying their countries’ flag were amazing, which is why we went on to look for an Iranian one as well. Even though we wanted to show our love for the Iranians, this proved to be a little bit more challenging than in Turkey, where even the kitchen towels and toilet paper (hmm, ok probably not) must have had a pattern of the Turkish red and white. In the bazaar of Tabriz, one of the largest in the country, we weren’t able to find one single flag for sale. After informing ourselves a bit about this with the locals, someone stated: the Turkish wear their pride from the outside, the Iranians only from the inside. Not accepting this reality, Jos decided to go for the first Iranian flag he could find, which was coincidentally attached to the roof of a shop. You can’t ask them for that, Stefan stated, but Jos was persistent. Yes we can, they will tell us no if they don’t want to, right? And indeed, it took a little bit of explaining (why on earth would those funny westerners want to have our Iranian flag), and the promise to send a Dutch and German flag once we got back home, before the shopkeeper climbed up his inventory to lower the flag and give it to us. We were so happy, and even though it was a bit oversized for our small jeep, we gratefully accepted this honor. After a few obligatory pictures and a thousand thanks, we left the shopkeeper wondering about what just happened to him, proudly carrying our Iranian green, white and red. Mission accomplished, we headed back to the hostel and, after connecting our flag to the reserve tire casing at the back of our car, called it a day.

The next day we decided to start our decent to the southern city of Esfahan, which was just out of reach in a day’s driving. This meant we had some time to drive east in the direction of the Caspian Sea, which was great as this is the home of some of Iran’s most scenic landscapes. Many people know Iran only as a mountainous and sandy country, but in a sense, it is the New Zealand of the central Asia: yes it has searing hot deserts, but also rocky mountains which even host some skiing resorts, green rain forest and beautiful sandy beaches. We drove a bit and before long we were driving along the Iranian border with Azerbaijan, a tourist hot spot for Iranians. Given that it was already getting dark, we decided to have some dinner at one of the many road side restaurants the region has to offer. We decided not to sit at one of the family benches (which would have meant that our dinner would be at the same elevation as our behinds we sat on, which is of course not one of the premier hallmarks of western civilization) but asked for a proper chair and table. After explaining that we didn’t want to have sheep meat (Jos practiced his extensive repertoire of animal sounds in order to make people clear that he didn’t have the stomach for anything other than chicken kebab) we waited patiently for our dinner. Two Azerbaijanis arrived carrying some local instruments and enthusiastically started playing their number one hit parade song called ching-ching-chinge-li-ding. They obviously were cutting corners at the end of a busy day, because after about 5 seconds of music they stopped and said la-la-la-money. Well ok, they used a bit of different wording, but the Hans Teeuwen (the Dutch comedian, not the famous astronaut) reference to lazy street musicians was spot-on here. After thanking them for their efforts, we had our decidedly mediocre dinner (what to expect at a road side restaurant in an Azerbaijani tourist region, right?) and went off into the night.

It took ages to wind down the hairpin-infested road down the mountains in the direction of the sea but after an hour or two we were finally back somewhere around sea level. The first thing that crossed our way was a police road block. Still a little bit worried that the Iranians at some point would find our little glass vodka bottles we tried to behave as normal as possible. When we actually got stopped our hearts started racing a bit, as our expectations of visiting Iran did not include spending a few nights in jail with two blokes called Abdul and Samir. As you can imagine, we were happily surprised when the police officer who knocked on our window had no intention of searching our car, and simply left us with a peach and a warm “welcome to my country”. After driving for a bit we decided that it was time to set up camp and empty some of our contraband. We drove into a small village to find some well-deserved peace, but soon found out that there were a few other people looking for the same. We drove and drove, even though the road got worse and worse and our GPS had long been telling us that there was no more road here. We drove into a small street and soon were greeted by the aggressive barking of a whole family of dogs, thereby waking the neighbors. We decided that this was not the quietness we were looking for and headed back to the road we came from. But the cars kept coming towards us, to the point where it became clear that ahead of us there was a giant illegal party (Iranians trying to do illegal stuff are also pretty much looking for something as remote as we were for our camp) going on or something of that nature. By now it was 2AM, so you can imagine we were surprised to find that there were still loads of people sitting outside in tiny villages selling melons and water. When we finally arrived at our camp site (we were well into the forest), we believed we were safe now. Imagine our surprise when, after five minutes, a local guy came up to us on his motorcycle to offer us a place to sleep. Given that we decided to empty one of our contraband bottles that evening, we politely declined and sat down for a well-deserved sip of highly illegal vodka-lemon.

The next morning we woke up far from fresh and fruity, but still needed to drive a good bit to get to the beautiful city of Esfahan. We went back over the same bumpy road we came from, which luckily was a lot easier to navigate than it had been the night before in the dark. When we got on the highway again, we were surprised by the cars and trucks we saw driving on the road: they all looked the same! There are 4 basic models which cover about 80% of all vehicles that can be found on Iranian highways: the Peugeot 405 passenger car (or the locally produced derivative, the Pars), the Zamyad (which is a kind of Iranian produced pickup truck, available only in blue), the Saipan Saba (a small mini sedan of Korean decent, only available in black and white) and a plethora of Mercedes utility vehicles (busses and trucks) from the ‘70’s, probably imported before the revolution of ’79. Especially the Mercedes vehicles caught our attention, as they looked old enough for the Mercedes museum with their retro bright orange or olive green colors, but were still driving like a champ (das beste oder nichts, remember Mercedes?). Another thing that caught our attention on the road, and violently so, were Iran’s speed bumps. My god, did they do a good job on those. We are generally used to being able to spot a speed bump about a mile away in Europe, where the speed bumps are generally equal in size, and either well-lit or colored white or something. In Iran, that is a different story. We imagined the Iranian highway planning team must have had a good laugh when designing their speed bumps, as they were the most ferocious car stoppers ever constructed by mankind. They are black as the asphalt they are lying on. They are tiny looking. And they are generally invisible to the naked eye (unless you’re standing at less than a meter distance). However, they are generally the size of a curb, about 20 centimeters high, and will make minced meat out of your springs, shocks and whatnot when driving anything faster than 10 kilometers per hour. The speed bumps are often (but not always) accompanied by road signs which announce their presence, however, given that these signs are also placed in places where there is no speed bump at all, we soon started to ignore these signs. And that’s when they hit you the hardest: BAM! The whole car was shaking, co-driver slammed into the dashboard, ugly sounds coming from the bottom of the car and from the shock absorbers.

Luckily we soon got the hang of it and started driving slower and slower, but that doesn’t mean we hit quite a few of them, scaring the hell out of us. That was not bad anyway, as the petrol we were able to buy on our trip through Iran was of pretty low quality. Given that, since the revolution, the international oil companies largely drew back from the country, there is a shortage of high-tech refining capability within the country, which means that the petrol available for purchase doesn’t meet the requirements for the basic Euro 95 norm. Oftentimes, the octane in the available petrol wasn’t even 90, but less, which meant that we couldn’t rev our engine over 3000rpm without endangering its health and longevity too much. Hence, it was always like a Russian roulette, trying to fill up the car. Another positive effect of us taking it slow was that we didn’t have to worry too much about the Iranian police, who were either standing at the side of the road holding laser guns (for speed measurement, not for picking a fight with passing unicorns), or were represented only by a cardboard image of their vehicle, trying to scare people into driving a bit more decently. At no point in time did they ever choose to bother us, and we were always greeted by a waving hand or another form of well-meant welcome. However, given the state of Iranian driver quality, a hard hand from the police is definitely required: these guys were driving like there was no tomorrow: it was not uncommon, for example, to see VIP busses pass us with well over 140 kilometers an hour or to see something like 6 cars next to each other at the traffic lights trying to get somewhere first (on a two lane road, that is). Those traffic lights, by the way, were an amazing source of disco vibe, as there were often so many of them next to, or on top of each other, blinking in every color of the rainbow without any consistently recognizable pattern. It was therefore always a bit exciting when driving past them: should we have stopped, were we simply warned, were the traffic lights out of order or broken, or could we simply ignore them altogether? There was no way of understanding their logic, which is why we generally chose to simply ignore them, and pass them slowly and diligently. An added advantage of our new-found slowness was that we were able to have a good look at the images of all the martyrs that died for their country: literally dozens upon dozens of them, about as many as we had seen Erdogans in Turkey, in every little village and town. Given that we didn’t pay enough attention during the history lessons about Iran, we had no idea who these people were, but imagined they must have done something spectacular for Iran either during the revolution of ’79 or during the violent war with Iraq that followed it throughout the ‘80’s.

We didn’t have a whole lot of time to further contemplate it, as we finally arrived in one of Iran’s most beautiful cities, the southern city of Esfahan. Given that Jos had a previous good experience there, we went to the same hostel: Amir Kabir, not too far from the historic city center and the magnificent bridges over the nearby river. It didn’t take very long before we noticed that this wasn’t going to be the same laidback and quite visit as four years ago, as the place was littered with rallyers and other tourists (we even saw the first Americans in Iran, which as you may know, are generally not the quietest chaps). A little bit disappointed about the first signs of mass tourism we checked into the hostel anyway, as we had decided it was time for a couple of days of relaxing, writing up blogposts and enjoying the beauty of the city. After having had a good rest (the trip to Esfahan took over 12 hours of driving in the burning heat), we chose to spend the day in the courtyard, getting in touch with family and checking social media. This is where we first met the French twins, let’s call them Claire & Antoinette, who were travelling Iran as well. We shared some of our first travel experiences and talked about how they felt as travelling women in a country generally not known for its liberal attitude towards woman. After having had a relaxing afternoon, we headed for the spectacularly photogenic Esfahan bridges, which are lit up throughout the night, in order to make some nice images.

As we arrived at the bridges it was sprawling with tourists, both local and in the form of a tour group of German seniors. We went along and started to walk around the bridges for some amazing pictures. At our first stop we were approached by what seemed to be pretty openly gay Iranian guys who wanted to have their picture taken by us. Showing your gayness has been something unheard of for a very long time in Iran (which still carries serious penalties, like being hung from a tree together with your mate), but on this evening in Esfahan, around every corner, on every dark park bench and behind every somewhat hidden tree, there seemed to be guys enjoying each other’s company a bit more than can be normally expected. In that sense, this was a major indicator of Iranians becoming a bit freer as time passes, which was very nice to see. Another example of this new-found freedom were the loads of people asking us for selfies, conversation or our phone numbers, which was a surprising experience (even to the point where we almost got tired from it). We were photographed with completely random people on the bridge, over 20 times that evening alone (even though Stefan had taken the effort to cover his decidedly attractive knees for the event). Posing young women, old men, children and whole families at the same time: it was as if we were movie stars for the evening! After having enjoyed a couple of cold fruity beverages and walked around the bridges for a few hours, we ended up in our final conversation for the night with two middle aged Iranian men on top of the central Esfahan bridge.

The most memorable thing of this conversation was not the standard obligatory questions about us or our countries (where is it actually, what job do you do there, where are your wives, etcetera), or even the request of one of the men to be offered a job by us (sorry, as we currently don’t run an international trucking company, it is a bit difficult for us to be handing out jobs on the spot to half-experienced Iranian drivers). No, the most memorable part came in the form of a string of google key words. You see, one of the guys, not the brightest bulb in the inventory, had asked us to have a look at his mobile phone, which “did not work” anymore. After suggesting a reset of the phone in order to make things work again, he offered us the phone and asked us to see what the issue was. Upon trying to start a google search for how to reset a virus-riddled Android phone, we found that the first tab in his browser contained the rather dubious and endearing search terms: “sex with nice woman” (in English). After subtly suggesting that his search behavior may have inspired Iranian cyber security forces, responsible for keeping the Iranian internet safe, fun and clean for everyone, to install some fancy viruses on his phone, we gave him a couple of tips on how to get his phone cleaned up and called it a night.

The lost iPhone

But life had one more surprise waiting for us on our way back to the hostel. Given that he was generally a bit suspicious of the taxi drivers, Jos decided to get out his phone in order to GPS us back. Upon arriving near the hostel, Jos paid the taxi driver, after which we got out. Tick-tack-tick-tack, f*ck. This time Stefan looked at Jos with a question mark over his head. My phone, I forgot my phone! Nooooo! What do we do, Stefan asked? Go back and find it, Jos said: I can’t even call my mother anymore without that thing. That’s where karma proved to be in our favor again, as a random car stopped next to the road, asking us if we needed help. Yes, please take us to the bridge, Jos shouted at the driver. Sure, hop on he said (well of course that’s not what he said, but we speak none of the local languages whatsoever, which can be Farsi, Turkish or Arab in Iran, which means we have no idea what his actual words were). Having crammed ourselves in the back of the small car we instructed the driver where we needed to go: back to the bridges. The driver raced through the city as if his life depended on it and before we knew it we were back at the place we left just fifteen minutes before. Stefan was cool enough to think straight and found the taxi driver back in his initial spot within seconds (Jos was so upset about losing his phone that he couldn’t even tell the taxi’s right color). Stefan tried to explain our issue to the taxi driver, who then pulled up the phone from the back seats: we’ve got it! About as confused as us, the taxi driver decided to drive us back to the hostel again, which was the end of our colorful night.

The big square in Isfahan

The next morning we were greeted by a wild orchestra of tourist voices in the courtyard at our hostel. After having been able to ignore it for an hour or two, we got up and found the two French sisters sitting there writing their post cards. We decided to go to the park together to relax a bit and go to out for some food later that night, together with a Korean girl who tagged along. After our dinner, we split up from the tired girls, and decided to go to the central square (next to the amazing Esfahani mosques). When we arrived there (it was already 10PM) the square was full with people, listening to what at first appeared to be an open air concert. After getting a bit closer we noticed actors running around as well, and before we knew it a nice Iranian guy was explaining us that we had landed at the recording of one of the most popular TV series in Iran.

The crowd was going wild, with people trying to climb over one another to get a glimpse of the decidedly romantic spectacle (there was singing, flowers and what not) that unfolded before our eyes. We looked at each other and decided this was a good opportunity to mingle with some more Iranians. We sat down together with them in the grass and enjoyed everything we saw around us. It didn’t take very long before the Iranians started to invite us for tea (everyone seemed to have brought a family picnic meal and tea cookers) and chat away. One of them, a man in his late 40’s tried to have a conversation with us, even though he didn’t seem to speak any English at all. Lucky for him, his wife seemed a bit more internationally oriented, and was able to translate everything that was said between us (although at no point did she directly talk with us, always telling her husband what he should mumble). After having thanked for the decidedly comical talk, we struck up another conversation with a couple of guys from Esfahan.

As Stefan exchanged some stories about working in Germany and the brewing of homegrown alcoholic beverages (which is apparently done by Iranians by fermenting non-alcoholic beer, which is freely available throughout the country, with some sugar in the bathtub at home) with our latest conversational partners, Jos decided to walk around a bit, in order to get some nice pictures of the filming that was going on. Given that there was a fence built around the outdoor studio that was set up, he moved his way through the crowds in order to get to the fence, and in no time he was able to get invited over it so he would have a better view. After taking a few quick pictures, he was greeted by the manager of the series, who then introduced him to one of the leading actors. Given that the filming was about done, Jos was able to get some pictures taken together with both the actor and the manager, just before they were stormed by hordes of Iranians who wanted to do the same. Luckily, Jos was just in time to get away from the massive crowds, and stumbled back to pick up Stefan in order to get back to the hostel. After a quick talk with a local student (who was determined to fire of as many questions as he could in the 5 minutes we had to spare) and an international student, a friendly Iranian who studied at a German university, we headed back for our well-deserved rest.

The next day was moving day again, because we were only at about half of the total distance we needed to travel in order to get to Ulan Batar. The next stop would be Yazd, which was the first city in the east we would cross. After having said our goodbyes to the people we met at the hostel, we loaded up our vehicle with water and set off. On our way, we were greeted by friendly Iranians all the way, which is something we had grown somewhat accustomed to by now. However, we also experienced a new, and rather dangerous, episode in terms of hospitality. Somewhere along the way, a guy was so happy to see us that he wanted to offer us some food. Given that we were on a fast lane, we decided it was too dangerous to stop there. However, this was not going to stop the hospitable Iranian from offering us some niceties, which he delivered to us by simply driving right next to us and handing us over a bag with what appeared to be (and tasted like) bird food (probably salted sunflower seeds) through the car windows while driving 100 kilometers an hour. Imagine that happening in Europe! Before long we crossed a beautiful old village, with houses completely built out of mud. Stefan saw his change and decided to make a couple of images, while Jos was being introduced to the local children, who all came running at us the moment we pulled over the car. After giving out some gummi bear candies and documenting the village we drove off, being followed by waving happy children.

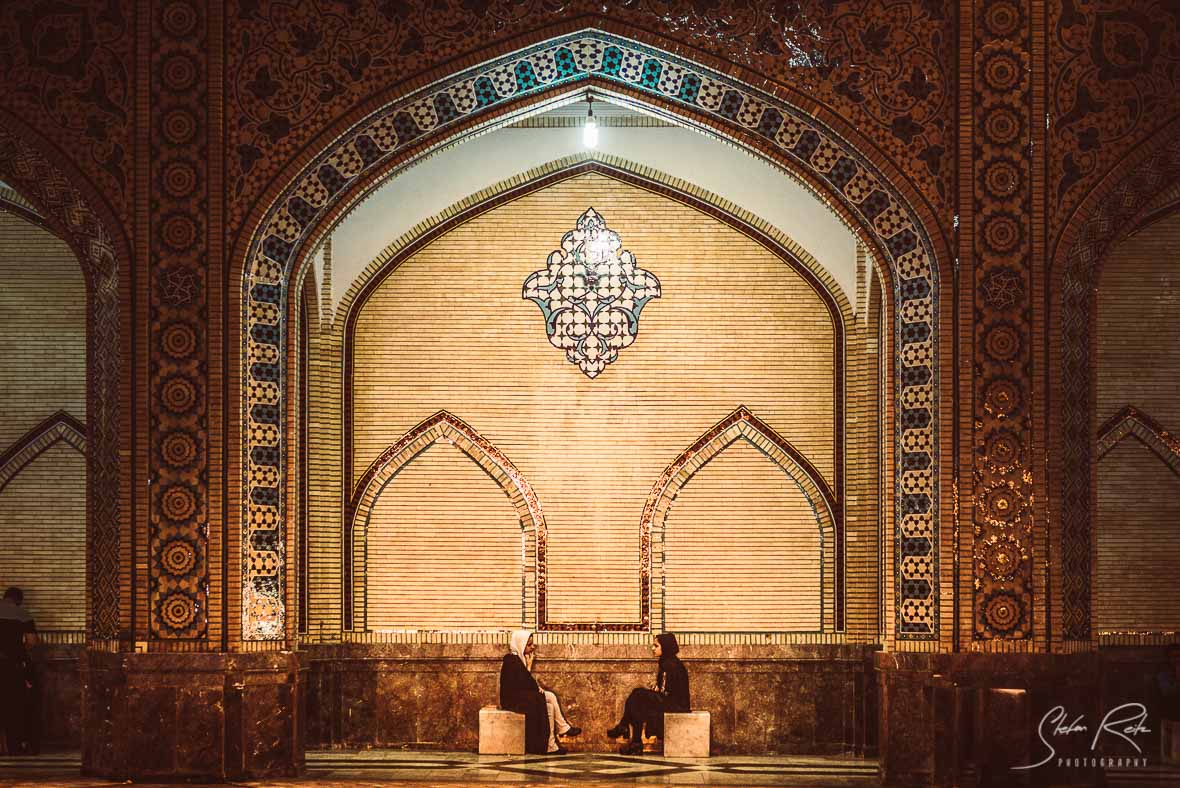

We continued our trip east and noticed that, although Yazd was not that far away from Esfahan, we were getting into the more conservative parts of Iran. Even though we had also seen women walking around without any headscarves whatsoever in Iran, in Yazd the common dress code for women was fully covered and black, which gave it a bit of an eerie feeling to walk around the city. Nevertheless, we walked around the old town a bit, in order to get a glimpse of the traditional cooling systems the Iranians have been building on top of their houses for hundreds of years. Walking through the tiny little maze of streets, we found a mosque, which we decided to enter once we were given the go-ahead by a visiting Muslim. After walking around a bit further we decided it was dinner time, which meant we had to find a restaurant again (which was not always that easy in Iran for some reason).

After some searching, we were helped by a local who showed us the little alley that led to a surreal LED-lit restaurant inside a hotel. Even though the environment was a bit comical, the chicken kebab we had was good as always. During dinner, we discussed our doubts about making it out of Turkmenistan in time, as our visa was about to go live and we only had been granted five days to transit this strict country. What would happen if our car broke down, requiring big repairs? What would happen if we were held up by the border control or the police, who wanted baksheesh? What would happen if the roads were worse than expected, forcing us to drive 20 kilometers an hour? In the end, we worked out some alternative solutions and promised ourselves that everything would be all right. One way or another, it was time to get to the last Iranian border city, Mashhad, as soon as we could. We had some final discussions with the waiter (who mistakenly asked us for 170 Dollar for two chicken kebabs instead of 17, confusing Iranian money and all) and headed off into the night.

On our way to the exit, we drove through the beautiful eastern Iranian landscapes, which started to look more and more like the images we had seen from Afghanistan. That wasn’t entirely surprising, given that we drove only 200 kilometers from its border. The grotesque mountains made the trip to Mashhad feel like we were travelling over the moon. One of the road signs we came across reminded us of the often funny English which was used in Iran: for example that we were on a “single file” road, that “miscell anus” people may not be allowed into the mosque and that the soup starter was called the “soup before food”, leaving in complete mystery exactly what was in it.

Mashhad

After our last stretch of Iran, we finally arrived in Mashhad, which had another surprise waiting for us. When driving into the city we noticed how massive it is, with cars and people coming at us from everywhere. A quick glance in our Lonely Planet taught us that Mashhad is actually Iran’s second biggest (after Teheran) and most religious city. And although its size was the first thing we were confronted with, the religious part was very soon to follow. When we finally found a parking spot near the holy shrine in the center of the city, we started walking around in order to find a decent hostel. Boy were we in for a surprise! Little did we know that the Shia Muslims had a holiday, which inspired them (en masse) to come to Mashhad to visit this holy place. This meant that every hotel, hostel, shared apartment and any other location which had a pillow and blanket had been booked out for weeks.

Hotel after hotel we contacted, whether they were found in our travel guide, maps apps or simply on the internet, were either non-existent anymore or booked from top to bottom, full with devout Muslims. It took us a persistent hour or two before we finally found a bed, which in this case was an overpriced room for a whole family of five. Happy to have found something at all, we dropped our bags and went for some dinner. The holy shrine was going to be our next stop, which is why we tried to find our way through the masses of devout Muslims which were swarming (still at 11PM) its outer courts. We soon noticed that we were looked at by some as if we were from Mars, this didn’t feel welcoming at all: this was not an appropriate place for atheists to visit, as Mashhad is (in small) to Shia Muslims what Mecca is to all Muslims. This meant that, even though about 20% of the people were still asking us for selfies, a much larger than expected portion of the people were either indifferent to us being there (50%) or worse, downright hostile (about 30%). Hence, it didn’t take long before we were sent away from the shrine by visiting Muslims, leaving us with little else to do to call it a night and go to sleep (which was an anti-climax to an otherwise very welcoming Iranian experience).

Iran in a week has been a lot of things to us: intense, too short, hilarious, beautiful and awe-inspiring, but most of all a very hospitable and decidedly interesting experience. We enjoyed every second of our tour through this magnificent country (thanks to dozens of helpful and friendly Iranians) and will soon be back here for more impressions.

Thank you Iran!